Sequencer Selection

Fernet

A protocol for random sequencer selection for the Aztec Network. Prior versions:

- Fernet 52 (Aug 2023)

- Sequencer Selection: Fernet (Jun 2023)

- Sequencer Selection: Fernet (Jun 2023, Forum)

Introduction

Fair Election Randomized Natively on Ethereum Trustlessly (Fernet) is a protocol for random sequencer selection. In each iteration, it relies on a VRF to assign a random score to each sequencer in order to rank them. The sequencer with the highest score can propose an ordering for transactions and the block they build upon, and then reveal its contents for the chain to advance under soft finality. Provers must then assemble a proof for this block and submit it to L1 for the block to be finalized.

Staking

Sequencers are required to stake on L1 in order to participate in the protocol. Each sequencer registers a public key when they stake, which will be used to verify their VRF submission. After staking, a sequencer needs to wait for an activation period of N L1 blocks until they can start proposing new blocks. Unstaking also requires a delay to allow for slashing of dishonest behavior.

Randomness

We use a verifiable random function to rank each sequencer. We propose a SNARK of a hash over the sequencer private key and a public input, borrowing this proposal from the Espresso team. The public input is the current block number and a random beacon value from RANDAO. The value sourced from RANDAO should be old enough to prevent L1 reorgs from affecting sequencer selection on L2. This approach allows each individual proposer to secretly calculate the likelihood of being elected for a given block with enough anticipation.

Alternatively, we can compute the VRF over the public key of each sequencer. This opens the door to DoS attacks, since the leader for each block becomes public in advance, but it also provides clarity to all sequencers as to who the expected leader is, and facilitates off-protocol PBS.

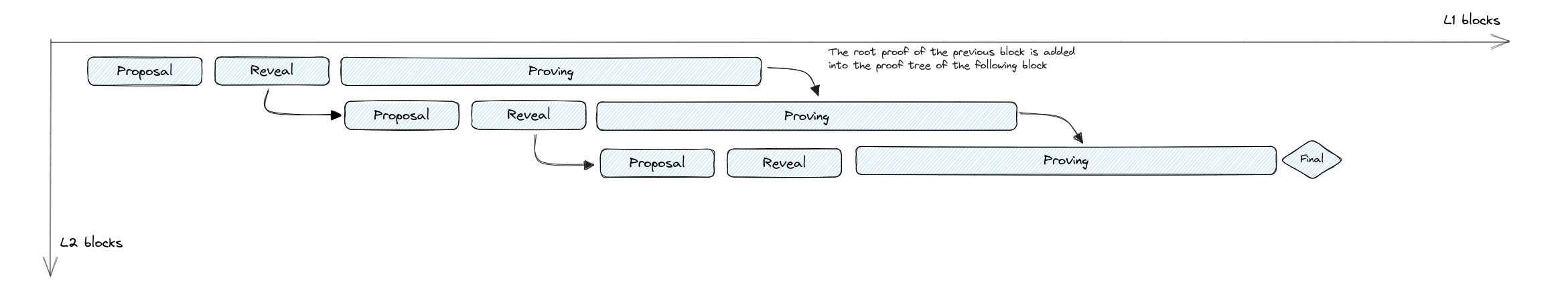

Protocol phases

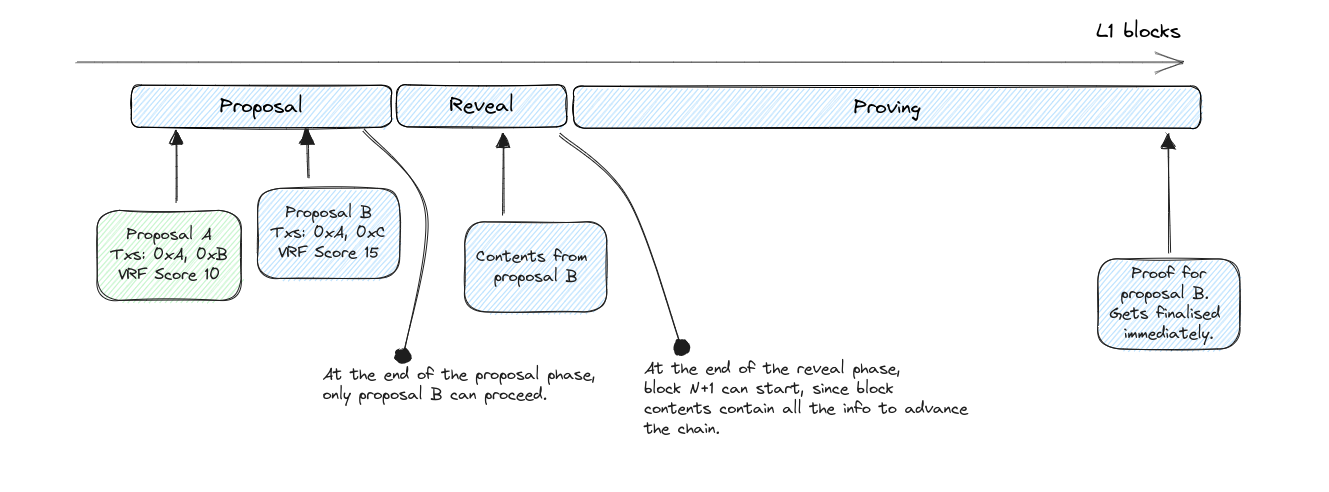

Each block goes through three main phases in L1: proposal, reveal, and proving. Transactions can achieve soft finality at the end of the reveal phase.

Proposal phase

During the initial proposal phase, proposers submit to L1 a block commitment, which includes a commitment to the transaction ordering in the proposed block, the previous block being built upon, and any additional metadata required by the protocol.

Block commitment contents:

- Hash of the ordered list of transaction identifiers for the block (with an optional salt).

- Identifier of the previous block in the chain.

- The output of the VRF for this sequencer.

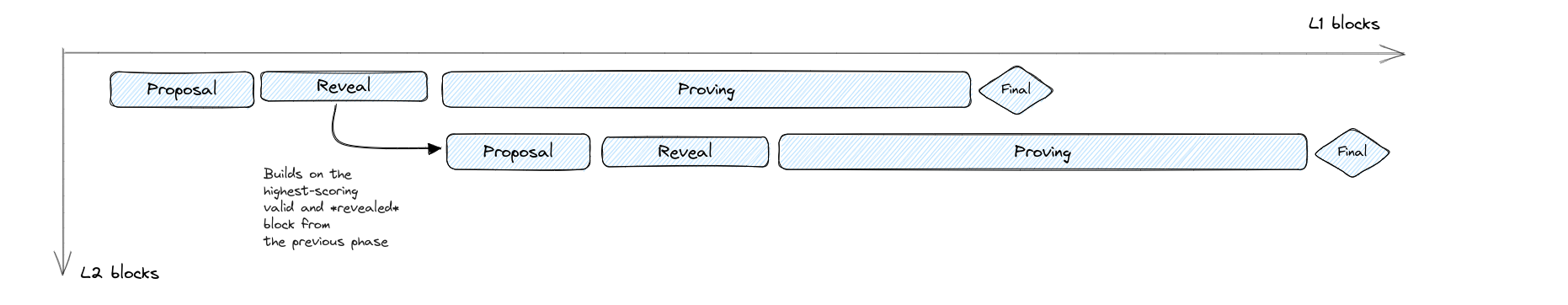

At the end of the proposal phase, the sequencer with the highest score submitted becomes the leader for this cycle, and has exclusive rights to decide the contents of the block. Note that this plays nicely with private mempools, since having exclusive rights allows the leader to disclose private transaction data in the reveal phase.

In the original version of Fernet, multiple competing proposals could enter the proving phase. Read more about the rationale for this change here.

Reveal phase

The sequencer with the highest score in the proposal phase must then upload the block contents to either L1 or a verifiable DA layer. This guarantees that the next sequencer will have all data available to start building the next block, and clients will have the updated state to create new txs upon. It should be safe to assume that, in the happy path, this block would be proven and become final, so this provides early soft finality to transactions in the L2.

This phase is a recent addition and a detour from the original version of Fernet. Read more about the rationale for this addition here.

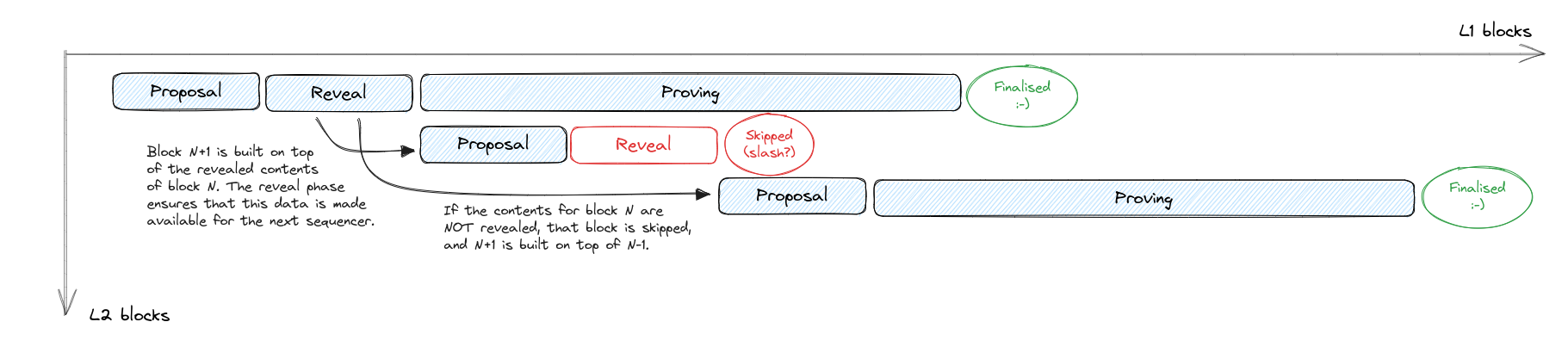

Should the leading sequencer fail to reveal the block contents, we flag that block as skipped, and the next sequencer is expected to build from the previous one. We could consider this to be a slashing condition for the sequencer.

Proving phase

During this phase, provers work to assemble an aggregated proof of the winning block. Before the end of this phase, it is expected for the block proof to be published to L1 for verification.

Prover selection is still being worked on and out of scope of this sequencer selection protocol.

Once the proof for the winning block is submitted to L1, the block becomes final, assuming its parent block in the chain is also final. This triggers payouts to sequencer and provers (if applicable depending on the proving network design).

Canonical block selection:

- Has been proven during the proving phase.

- Its contents have been submitted to the DA layer in the reveal phase.

- It had the highest score on the proposal phase.

- Its referenced previous block is also canonical.

Next block

The cycle for block N+1 (ie from the start of the proposal phase until the end of the proving phase) can start at the end of block N reveal phase, where the network has all data available on L1 or a DA to construct the next block.

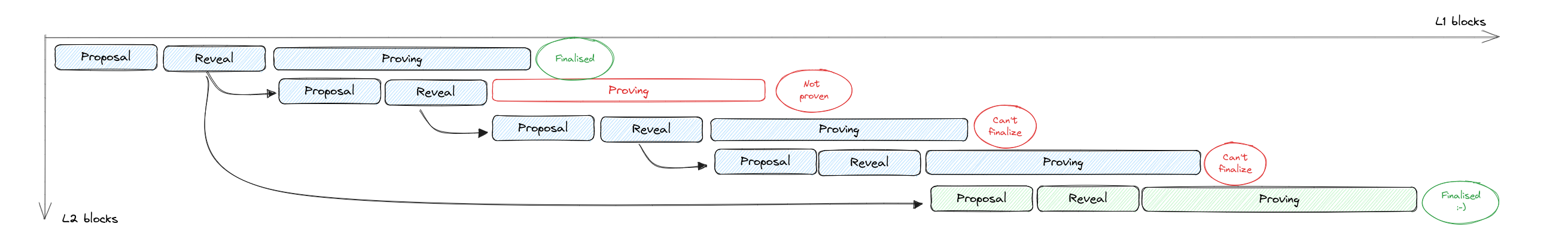

The only way to trigger an L2 reorg (without an L1 one) is if block N is revealed but doesn't get proven. In this case, all subsequent blocks become invalidated and the chain needs to restart from block N-1.

To mitigate the effect of wasted effort by all sequencers from block N+1 until the reorg, we could implement uncle rewards for these sequencers. And if we are comfortable with slashing, take those rewards out of the pocket of the sequencer that failed to finalize their block.

Batching

Read more approaches to batching here.

As an extension to the protocol, we can bake in batching of multiple blocks. Rather than creating one proof per block, we can aggregate multiple blocks into a single proof, in order to amortize the cost of verifying the root rollup ZKP on L1, thus reducing fees.

The tradeoff in batching is delayed finalization: if we are not posting proofs to L1 for every block, then the network needs to wait until the batch proof is submitted for finalization. This can also lead to deeper L2 reorgs.

In a batching model, proving for each block happens immediately as the block is revealed, same as usual. But the resulting proof is not submitted to L1: instead, it is aggregated into the proof of the next block.

Here all individual block proofs are valid as candidates to finalise the current batch. This opens the door to dynamic batch sizes, so the proof could be verified on L1 when it's economically convenient.