Concepts

This page outlines Aztec's fundamental technical concepts.

Aztec Overview

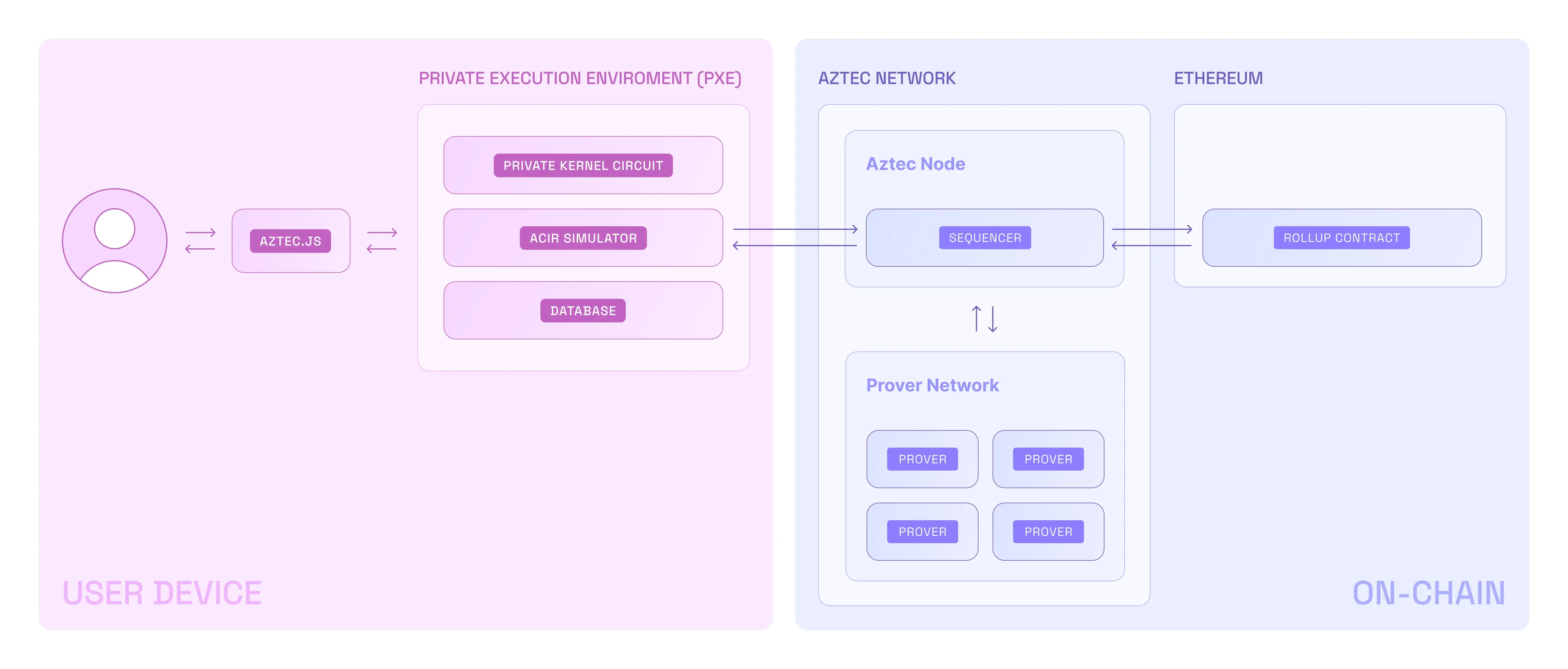

- A user interacts with Aztec through Aztec.js (like web3js or ethersjs)

- Private functions are executed in the PXE, which is client-side

- They are rolled up and sent to the Public VM (running on an Aztec node)

- Public functions are executed in the Public VM

- The Public VM rolls up the private & public transaction rollups

- These rollups are submitted to Ethereum

The PXE is unaware of the Public VM. And the Public VM is unaware of the PXE. They are completely separate execution environments. This means:

- The PXE and the Public VM cannot directly communicate with each other

- Private transactions in the PXE are executed first, followed by public transactions

Private and public state

Private state works with UTXOs, or what we call notes. To keep things private, everything is stored in an append-only UTXO tree, and a nullifier is created when notes are invalidated. Nullifiers are then stored in their own nullifier tree.

Public state works similarly to other chains like Ethereum, behaving like a public ledger. Public data is stored in a public data tree.

Aztec smart contract developers should keep in mind that different types are used when manipulating private or public state. Working with private state is creating commitments and nullifiers to state, whereas working with public state is directly updating state.

Accounts

Every account in Aztec is a smart contract (account abstraction). This allows implementing different schemes for transaction signing, nonce management, and fee payments.

Developers can write their own account contract to define the rules by which user transactions are authorized and paid for, as well as how user keys are managed.

Learn more about account contracts here.

Smart contracts

Developers can write smart contracts that manipulate both public and private state. They are written in a framework on top of Noir, the zero-knowledge domain-specific language developed specifically for Aztec. Outside of Aztec, Noir is used for writing circuits that can be verified on EVM chains.

Noir has its own doc site that you can find here.

Communication with Ethereum

Aztec allows private communications with Ethereum - ie no-one knows where the transaction is coming from, just that it is coming from somewhere on Aztec.

This is achieved through portals - these are smart contracts deployed on an EVM that are related to the Ethereum smart contract you want to interact with.

Learn more about portals here.

Circuits

Aztec operates on three types of circuits:

- Private kernel circuits, which are executed by the user on their own device and prove correct execution of a function

- Public kernel circuits, which are executed by the sequencer and ensure the stack trace of transactions adheres to function execution rules

- Rollup circuits, which bundle all of the Aztec transactions into a proof that can be efficiently verified on Ethereum

What's next?

Dive deeper into how Aztec works

Explore the Concepts for a deeper understanding into the components that make up Aztec:

🗃️ Accounts

2 items

🗃️ Wallets

1 items

🗃️ Storage

1 items

🗃️ Smart Contracts

5 items

📄️ Transactions

On this page you'll learn:

🗃️ State Model

1 items

🗃️ Private Execution Environment (PXE)

1 items

🗃️ Circuits

2 items

🗃️ Nodes and Clients

1 items

Start coding

Follow the developer getting started guide.